Montreal's Cultural and Artistic Heritage

Andrea Winterhalter

A Francophone city par excellence in an essentially

English-speaking country, Montréal surprises through its uniqueness, which is best

reflected in the city's artistic and cultural landscape.

A Francophone city par excellence in an essentially

English-speaking country, Montréal surprises through its uniqueness, which is best

reflected in the city's artistic and cultural landscape.

What we see today in Montréal in terms of arts and culture

is the product of the age-old confrontation between its two principle

communities, representatives of two powerful nations: Great Britain and France.

For more than two centuries, these two communities - the Anglophones and the

Francophones - have asserted their domination in turns depending on the

position each held in the economic, social and political life of the city at a

given time. Although their coexistence was not always peaceful, these two

ethnic groups with opposite life styles and outlooks have each contributed in

its own way to shaping the face of the city.

Rivals and allies at the same time, they transformed their city together, turning it into a place that stands out through its cultural and artistic background as no other city does.

Anglophones and Francophones over Time

Montréal, the small mission colony founded by the French military officer Paul Chomedy, Sieur de Maisonneuve in 1642 surrendered to the British troops in 1760. Its fate, and that of all French Canadians, was sealed three years later, in 1763, when France transferred its colonies to Britain. From this point forward, Francophone Montréalers would have to share their space with people whose language, religion and laws had nothing in common with their own (Lacoursière 55-58).

In the early days following the conquest, the Anglophones in Montréal accounted for only a very small percentage of the city's population and they were almost completely assimilated by the French-speaking community. The situation started to change in the 1780s when American traders, most of them of Scottish or Irish descent, came to Montréal because of its flourishing fur trade (Cooper 7-8).

The waves of immigrants that arrived in the early 19th century from the British Isles also contributed to transforming Montréal's English-speaking community into a majority, a phenomenon that lasted until the 1860s. Many of these new-comers were destitute, but others belonged to the upper classes and had brought with them the know-how and financial resources that would help the city prosper (Cooper 18-20; Roberts 143).

All through the 1870s, the dominating figures that drove Montréal's economic development belonged in fact to the English-speaking community (Roberts 246). It was the wealthy Anglophone entrepreneurs that founded, for instance, the Bank of Montréal (1817) and McGill University (1821), and financed the construction of the Lachine Canal (1825) (Rémillard and Merret 14). Unlike their wealthy Anglophone fellow citizens, French Canadians occupied an insignificant position in the city's economy, most of them working for the English-speaking business owners (Linteau, Durocher, and Robert 405). The few well-to-do French-speaking families turned rather to the Church, the professions and politics (Roberts 149, 246).

Divisions, however, did not follow rigid lines. As Leslie Roberts states, "[b]anking, for example, rapidly became an occupation for both French- and English-speaking financiers and their employees. The retail trade was mainly in the hands of the French; wholesaling was divided between Scottish and French elements; manufacturing ... was largely, but by no means entirely, in the hands of English-speaking owners" (248).

At the beginning of the 20th century, as Montréal attracted more and more French Canadians from the neighbouring regions, the English-speaking community soon found itself in the position of a minority, making up only one third of the city's population (Cooper 92, Roberts 260). French Canadians had emerged as the dominant community and they were consolidating their presence, whereas English Canadians were losing ground. The French-Canadian bourgeoisie was now on the rise; intellectuals, journalists, and professors gained more influence and had a say in the city's cultural life (Cooper 130-31).

The structure of the city's population changed even more after the 1920s. As people belonging to various other ethnic groups added to the city's two main communities over the years, they disturbed the ethnic and religious division that had existed up to that time and turned Montréal into a cosmopolitan metropolis, where pluralism has slowly replaced domination and submission.

Although each group deserves recognition for the significant part it has played in the city's development, this paper will focus only on the contributions of French-speaking Canadians and English-speaking Canadians of English, Scottish and Irish origin to the city's architectural heritage and public art, and to the development of fine arts.

Architectural Styles in Montréal

Montréal's architectural heritage reflects the evolution of the city's two main communities and bears the marks of the social status and preferences each of these two ethnic groups had over time. Its richness of forms and styles comes precisely from the fact that the city was the meeting ground of two different nations that followed different European models in architecture (Marsan 92).

During the French Régime, for instance, the Francophones preferred a utilitarian architecture, which best responded to their needs and made use of the building materials readily available in the area. Some of these buildings, such as Maison Saint-Gabriel and Château Ramezay still stand today, reminding of the architecture typical of north-western France (Rémillard and Merrett 20, Marsan 60).

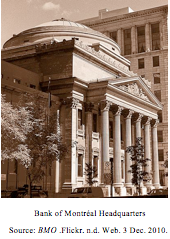

After the conquest, the British brought in their own

styles. Thus, in the early 19th century, new buildings in the Neo-Classical

style added to or replaced old French Régime buildings and soon gave the French city an

Anglo-Saxon character (Maurault 124, Rémillard and Merrett 37). At first

restricted to institutions, the new architectural style rapidly spread to

commercial and residential buildings as well, reflecting the preoccupation of a

dominant Anglophone class with its own image of wealth and with the appearance of the city

(Marsan 60). Examples include the Old Customs House (1836), the headquarters of

the Bank of Montréal (1845), and the Bonsecours Market (1845-52) (Rémillard and

Merrett 37-44).

After the conquest, the British brought in their own

styles. Thus, in the early 19th century, new buildings in the Neo-Classical

style added to or replaced old French Régime buildings and soon gave the French city an

Anglo-Saxon character (Maurault 124, Rémillard and Merrett 37). At first

restricted to institutions, the new architectural style rapidly spread to

commercial and residential buildings as well, reflecting the preoccupation of a

dominant Anglophone class with its own image of wealth and with the appearance of the city

(Marsan 60). Examples include the Old Customs House (1836), the headquarters of

the Bank of Montréal (1845), and the Bonsecours Market (1845-52) (Rémillard and

Merrett 37-44).

As Scottish immigrants made up a significant part of the Anglophone community and played key roles in the city's economy (Linteau, Durocher, and Robert 43), they would equally contribute to the city's urban landscape, but through buildings in the revived Gothic style, such as the Church of St. Paul of Scotland (1867).

Francophones also took an interest in this type of architecture and used it for some of their churches, such as the Église Saint-Pierre-Apôtre, a remarkable example of unity and strength (Marsan 94).

In general, though, church architecture bore the marks of the rivalry between French-speaking and English-speaking Montréalers, who did not share the same religion. Thus, for instance, in a period in which Anglicans used the Gothic style, Francophone Roman Catholics found themselves forced to resort to a different style in order to assert their character. This style, the Romanesque, represented the trademark of French-Canadian Catholicism until 1885. Examples of such buildings are the Chapel of the Grey Nun's Convent and the Chapel of Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes (Rémillard and Merrett 79-81).

Additionally, French Canadians had a preference for the Second Empire and Beaux-Arts styles, both originating from France. In the latter part of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, the rising French-Canadian bourgeoisie used these styles in a desire to return to their French roots and assert their connection with France. Two examples of buildings in these styles are respectively Montréal City Hall and the Archives Nationales du Québec (formerly the Ecole de Hautes études commerciales).

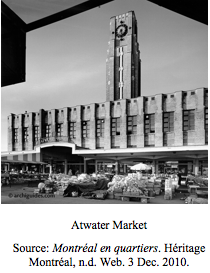

The first half of the 20th century belonged to the Art Deco

and Art Moderne styles, both from France. French-Canadian architects "saw in

Art Deco the cultural vitality of the mother country and the innovative freedom

of America. It was the perfect style to express the fundamental duality of

the French nation in the new world ... " (Rémillard and Merrett 182). Examples of

buildings in the Art Deco style are the Université de Montréal, Atwater Market

and the Main Pavilion of the Botanical Gardens (Rémillard and Merrett 182-190).

The first half of the 20th century belonged to the Art Deco

and Art Moderne styles, both from France. French-Canadian architects "saw in

Art Deco the cultural vitality of the mother country and the innovative freedom

of America. It was the perfect style to express the fundamental duality of

the French nation in the new world ... " (Rémillard and Merrett 182). Examples of

buildings in the Art Deco style are the Université de Montréal, Atwater Market

and the Main Pavilion of the Botanical Gardens (Rémillard and Merrett 182-190).

After the Second World War, architecture no longer served as a mirror of the communities' status in the city. Focus shifted instead to values such as progress, freedom and democracy, symbolised in architecture through the purity of forms, linearity, transparency, and rationalism (Gympel 96).

Public Art in Montréal

Montréal's two "majorities," the Anglophones and the Francophones, expressed their identity not only through the architectural styles they chose for their buildings, but also through the works of public art they left for future generations. The oldest forms of public art in Montréal are monuments and memorials in the form of commemorative plaques or bronze statues mounted on a stone base and generally set up in parks, squares, or cemeteries. Accessible to everybody in the city, these works of art made a statement: they showed which community held a higher position in the city. Consequently, they often reflected the rivalry between the two communities and their efforts to assert their identity, as each group used them as tools to recognize the achievements of one of their members or an important event in their history (Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal 9-10).

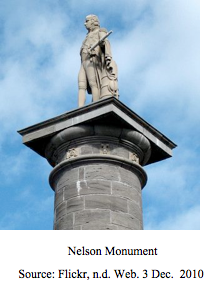

One of the first monuments in Montréal is the Nelson column

in Place Jacques Cartier, inaugurated in 1809 (Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal 12) by

the English merchants of the city in memory of Admiral Nelson's victory against

the French and the Spanish at Trafalgar. Erected in the heart of the city, the

statue illustrates the attempts of British colonists to establish their

position in the city and remind the French of their defeat (Manzagol and Bryant

ed. 43).

One of the first monuments in Montréal is the Nelson column

in Place Jacques Cartier, inaugurated in 1809 (Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal 12) by

the English merchants of the city in memory of Admiral Nelson's victory against

the French and the Spanish at Trafalgar. Erected in the heart of the city, the

statue illustrates the attempts of British colonists to establish their

position in the city and remind the French of their defeat (Manzagol and Bryant

ed. 43).

Along the same lines, Anglophone Montréalers also celebrated other events and people important to the English-speaking community. During the Victorian era, for instance, they asserted their ties with Britain by erecting monuments in honour of the queen to celebrate her contribution to economic and scientific progress, and to the development of arts and culture. One of these monuments is the statue of Queen Victoria unveiled in Victoria Square in 1872. Formerly called Place du Marché-à-Foin and later Place des Commissaires, the square was at the center of a heated debate between Anglophones, who wanted to change its name into Victoria Square to honour the queen, and Francophones, who vehemently opposed the idea. Eventually, the statue gave its name to the square and marked the victory of the Anglophones over the formerly French-Canadian site (Gordon 80-83).

In 1895, in Dominion Square (today's Place du Canada), the Anglophones built a monument dedicated to Sir John A. Macdonald - Father of Confederation and Canada's first prime minister. Francophone Montréalers, did not take long to respond and, approximately one month later, they inaugurated a monument in memory of Paul Chomedy de Maisonneuve, the man who had laid the foundations of the city. Ironically, the ceremony took place on July 1st, the anniversary day of the Confederation, and just one month after the inauguration of the Macdonald monument (Gordon xi-xiii).

Later, in 1916, French Canadians unveiled the statue of George-Étienne Cartier, "their own Father of Confederation" (Gordon 85), the man who had persuaded French Canada to enter the Confederation. By joining the Confederation, French Canadians got their province back and thus stood a better chance of preserving their language and culture.

Francophone Montréalers also honoured other historical figures that had fought for the survival of the French element. Thus, the Monument aux Patriotes, erected in 1926, is dedicated to the Patriotes of 1837-1838 (Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal 13), who rose against the British government and pushed for reform. The monument proudly stands at the corner of Notre-Dame and de Lorimier streets as a symbol of French-Canadian liberty.

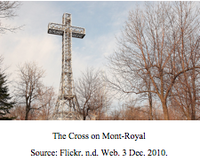

However, probably the most symbolically charged monument in

Montréal remains the Cross at the top of Mont-Royal, erected by Montréal's

French Canadians in 1924 to commemorate the cross set up in the same place by

Paul-Chomedy de Maisonneuve. Thirty meters tall and visible from 80 kilometres

away, the Cross dominates the metropolis and "marks the symbolic appropriation

of the city by French speakers" (Mount Royal, a Territory to Discover).

However, probably the most symbolically charged monument in

Montréal remains the Cross at the top of Mont-Royal, erected by Montréal's

French Canadians in 1924 to commemorate the cross set up in the same place by

Paul-Chomedy de Maisonneuve. Thirty meters tall and visible from 80 kilometres

away, the Cross dominates the metropolis and "marks the symbolic appropriation

of the city by French speakers" (Mount Royal, a Territory to Discover).

Unlike earlier public monuments, which had a nationalist character and celebrated important events or people in the history of a community, the works of public art produced in Montréal after the 1950s focus, under the influence of modernism and post-modernism, on issues that preoccupy the larger community of the city, irrespective of its Anglophone or Francophone roots (Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal 17). One example is the work of art commissioned by Concordia University in 1992 for its new library building. The installation, entitled An Explosion of Letters, consists of several separate elements displayed in the entrance hall and inside the library. The pieces feature letters and signs, symbols that make reference to knowledge, learning and multiculturalism (Rose-Marie Goulet with Effets Public).

The Development of Fine Arts in Montréal

By the 1860s, Montréal's Anglophone community had turned the city into the country's economic center and into a hub for maritime and railway transportation. All the great financial institutions of the country had their offices in Montréal. Nevertheless, although the city experienced an economic boom at the time and although it had a number of wealthy art lovers and art collectors, it lacked a school of art and a museum where artists could exhibit their works (The Museum).

The man who changed the situation was William Notman, a

Scot who had immigrated to Montréal in the summer of 1856. A few months after

his arrival, he opened a photography studio and in a short period of time found

international fame through his art. One of his most important achievements,

however, was the creation of the Art Association of Montréal in 1860 (Triggs).

Supported by artists and art collectors, mainly wealthy Anglophone

entrepreneurs, the Association stood out as the first group in Canada to

organize annual painting and photograph exhibitions meant to stimulate Montréal's

artistic environment (Karel 74, 136). It also established its own art school

and, with the help of one of its members from whom it received a plot of land,

money and a collection, it founded a museum. This museum would later become the

Montréal Museum of Fine Arts (The Museum).

The man who changed the situation was William Notman, a

Scot who had immigrated to Montréal in the summer of 1856. A few months after

his arrival, he opened a photography studio and in a short period of time found

international fame through his art. One of his most important achievements,

however, was the creation of the Art Association of Montréal in 1860 (Triggs).

Supported by artists and art collectors, mainly wealthy Anglophone

entrepreneurs, the Association stood out as the first group in Canada to

organize annual painting and photograph exhibitions meant to stimulate Montréal's

artistic environment (Karel 74, 136). It also established its own art school

and, with the help of one of its members from whom it received a plot of land,

money and a collection, it founded a museum. This museum would later become the

Montréal Museum of Fine Arts (The Museum).

As the Anglophone community generally enjoyed a higher status in the city and possessed substantial financial resources to found and maintain institutions that could contribute to the advancement of human knowledge, it managed to establish domination over French Canadians in the city's cultural and artistic life. However, this domination that lasted almost until the end of the 19th century did not mean that Francophones remained completely inactive. On the contrary, they also had outstanding representatives, who fought for the development of the French element. One of these figures was Napoléon Bourassa. A pioneer in the field of arts and letters, Bourassa was not only a sculptor, an architect and the first accomplished French-Canadian painter, but also the most important art critic of his time. Always an idealist, he also contributed to founding an association, an institute and a society whose aim was to promote the development of fine arts (Karel 74-77).

French-Canadian art gained momentum in the 1930s when several great painters emerged on Montréal's art scene. Two of these painters, Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté and Jean-Paul Lemieux, produced innovative works and enhanced the reputation of Montréal art schools, becoming two of the most important artists in Canadian art history (Cambron et al. 57). Additionally, due to his position as member of the teaching staff at the École de Beaux-arts de Montréal, Lemieux was able to promote a new generation of French-Canadian artists. Through his sustained pictorial research, Lemieux also contributed to modernizing the French-Canadian painting tradition, opening it up to new themes, such as the human being with its passions and preoccupations, modern life, the city, and the urban world (Carani et al. 75-6).

On the Anglophone side, John Lyman, a

painter, critic and activist, also made an important move towards modernity in

art by encouraging painters to abandon nationalist themes, such as traditional

rural Quebec scenes, and open up to modern European values in painting instead.

Even more significant remains the fact that Lyman, an artist belonging to the

Anglophone elite, joined Paul-Émile Borduas, a Francophone painter, to form the

Contemporary Arts Society with an aim to educate the Montréal public and to

increase its awareness of modern art (The Edmonton Art Gallery 6, 8, 12)

because modernity in art called for the modernization of its recipients, who

had to stop viewing art as a means of asserting their identity and start

viewing it as an entity in itself (Carani et al. 11-3).

On the Anglophone side, John Lyman, a

painter, critic and activist, also made an important move towards modernity in

art by encouraging painters to abandon nationalist themes, such as traditional

rural Quebec scenes, and open up to modern European values in painting instead.

Even more significant remains the fact that Lyman, an artist belonging to the

Anglophone elite, joined Paul-Émile Borduas, a Francophone painter, to form the

Contemporary Arts Society with an aim to educate the Montréal public and to

increase its awareness of modern art (The Edmonton Art Gallery 6, 8, 12)

because modernity in art called for the modernization of its recipients, who

had to stop viewing art as a means of asserting their identity and start

viewing it as an entity in itself (Carani et al. 11-3).

The decisive step in this direction was taken in the late 1940s and early 1950s when Montréal's Francophone community reasserted itself in the field of arts after having been kept in the shadow by the Anglophone community for a century and a half. Francophones initiated the Automatiste revolution - the most important and progressive artistic movement in Canada - which, on the one hand gave Canadian art a new dimension, and on the other hand produced the Refus global manifesto. This manifesto, released in Montréal in 1948, had a deep and long-term impact on Quebec society from an artistic, ideological and political point of view. The artists who had signed it aimed to transform society through art, break away from tradition, and free the spirit from any moral and religious prejudice (Carani et al. 8-10, 77-79). The manifesto thus became a sign of political and social revolution that claimed for a radical change in people's mentalities. Consequently, it met with a strong negative reaction not only from the Roman-Catholic Church, which could not accept that its precepts be ignored or opposed, but also from the conservative and nationalist State, which did not agree with the internationalist tendencies of the Automatistes. The ideas contained in Refus global were so revolutionary at the time, that Quebec needed ten years and the Quiet Revolution before it was ready to accept them.

In the 1950s, under the Drapeau administration, Francophones went even further to ensure the advancement of arts and culture in their city. Thus, they created in 1956 the Conseil des arts de la région métropolitaine - the very first arts council in Canada. The council, at present called Conseil des Arts de Montréal, has the mission to focus on contemporary art practices, to make the arts accessible to the public irrespective of its ethnic background, and to promote cultural diversity and treasure the city's communities for their uniqueness (Brief History).

Conclusion

Nowadays, the field of arts and culture no longer constitutes a site of competition for the city's communities. Instead, it has become a means of conciliation, an instrument that can bring Anglophones and Francophones together. Thus, Montréalers, regardless of their ethnicity, take part without prejudice in the city's cultural and artistic events, such as art exhibitions and numerous festivals. These events fascinate Anglophones and Francophones alike and act as a social, ethnic and racial conciliator because they require open-mindedness, emotional participation and intellectual curiosity, which are not the prerogatives of an ethnic group, but of the human being itself. Anglophones and Francophones have opposed and offset each other until they have come to construct a dual reality without which Montréal's cultural and artistic life would be unconceivable. Today, however, in contact with the city's art and culture, Montréalers no longer seek to assert their Anglophone or Francophone identity, but accept each as part of the reality they live in.

Works Cited

Brief History. Conseil des arts de Montréal, n.d. Web. 28 Nov. 2010.

Cambron, Micheline, et al. La vie culturelle à Montréal vers 1900. Canada: Les Éditions Fides Bibliothèque nationale du Québec, 2005. Print.

Carani, Marie et al. Des lieux de mémoire. Identité et culture modernes au Québec. 1930-1960. Canada: Les Presses de l'Univérsité d'Ottawa, 1995. Print.

Cooper, John Irwin. Montreal, A Brief History. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1969. Print.

Gordon, Alan. Making Public Pasts. The Contested Terrain of Montréal's Public Memories 1891-1930. Canada: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2001. Print.

Karel, David. Peinture et société au Québec. I. 1603-1948. Canada: Les Presses de l'Univérsité Laval, 2005. Print.

Lacoursìere Jacques. Histoire du Québec. Des origines à nos jours. France: Nouveau monde éditions, 2005. Print.

Linteau, Paul-André, René Durocher, Jean-Claude Robert. Quebec. A History. 1867-1929. Trans. Robert Chodos. Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, Publishers. 1983. Print.

Manzagol, Claude, Christopher R. Bryant. Montréal 2001: Visages et défis d'une métropole. Montréal: Les Presses de l'Univérsité de Montréal, 1998. Print.

Marsan, Jean-Claude. Montréal. Une esquisse du futur. Québec: Institut québécois de recherché sur la culture, 1983. Print.

Mount Royal, A Territory to Discover. Les amis de la montagne, n.d. Web. 28 Nov. 2010.

Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal. Les artistes dans la ville. Montréal: Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, 1992. Print.

Rémillard, François, Brian Merrett. Montréal Architecture. A Guide to Styles and Buildings. Trans. Pierre Miville-Deschênes. Sainte-Adèle, Québec: Les Éditions Café Crème, 2007. Print.

Roberts, Leslie. Montreal. From Mission Colony to World City. Toronto: Macmillan Company of Canada, 1969. Print.

Rose-Marie Goulet with Effets Public. Concordia University, 2010. Web. 1 Dec. 2010.

The Edmonton Art Gallery. The Contemporary Arts Society. Montréal. Edmonton: The Edmonton Art Gallery, 1980. Print.

The Museum. The Montréal Museum of Fine Arts, 2010. Web. 28 Nov. 2010.

Triggs, Stanley G. "The Man and the Studio. The Businessman and His Network." The Photographic Studio of William Notman. McCord Museum of Canadian History, 2005. Web. 25 Nov. 2010.

Leave a comment