Last year I had the privilege of hearing a talk delivered by a young man at the secondary school where I teach. Shaun Perrier has Asperger Syndrome, and he gave the talk - on his own initiative - to his peers at the school, to let them know what it is like to have Asperger's. The syndrome is an autism spectrum disorder characterized by difficulties with social interaction due to an inability to catch nuances in others' words and body language, and a similar lack of nuance of their own - a lack of facial expression, and speaking in a monotonous or overly formal manner. It is also characterized by a need to have a highly controlled environment, with a fixation on repetitive routines or rituals, as well as clumsiness. I was teary-eyed listening to the struggles that Shaun had gone through in his life and deeply impressed by how much he had overcome, and my heart went out to him and others like him, who deserve every opportunity to succeed that society can give them.

Shaun is now in CEGEP, but in high school, he was fully integrated in regular classrooms. He had an attendant who would help him get himself set up with the work and then either stay or go on to other classes to help other students. Attendants have no particular training; they are just there to help the students to whom they are assigned to stay on task, and also to help them with behaviour issues and social interactions. Academically Shaun had no problems; he was both intelligent and studious. His issues were more in relation to getting his routines set up and occasionally in his interactions with the other students.

Shaun was part of what is known as inclusive education, in which students with special educational needs are included in regular classrooms if at all feasible. The recent trend in Canada has been to practice inclusion to the greatest extent possible, and while education is a provincial jurisdiction, all the provinces have the same commitment to inclusive education (O'Donnell 130). The push for inclusive education began in the 1980s, and "in Canada, this push for reform was supported by the equality provisions of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which came into force in 1985. Since then the push for...inclusion has become an on-going element of educational politics in Canada" (Porter).

However, inclusive education is a controversial issue: some people believe inclusion is the best approach to education, both for special needs students and for society as a whole, while others believe that all students are best served when special needs students have separate classrooms. Nevertheless, inclusion is more and more the way that education is being carried out in Canada, and anything that concerns elementary and secondary education concerns everyone in society, because "children are our future," as the late great Whitney Houston reminded us.

Types and Rate of Disabilities in Canada

In a recent North American study, schools reported that 10-12% of students have some kind of disability (Jordan). The Quebec Ministry of Education classifies special needs students in three categories: handicaps, social maladjustments and learning disabilities. (Shaun has social maladjustments but not handicaps or learning disabilities.) Listed below are the disabilities as classified by Statistics Canada, including the percentage of disabled students who have those particular conditions. (The percentages add up to more than 100% because some disabled students have more than one disability.)

65% learning disabilities such as attention problems, hyperactivity and dyslexia

32% psychological, emotional or behavioural conditions

30% developmental disorders such as autism or Down syndrome

There are also sight, hearing, speech, mobility and dexterity conditions, as well as chronic conditions such as asthma, severe allergies, heart condition, cancer, epilepsy, cerebral palsy, etc. If the chronic conditions do not cause activity limitations, they are not considered disabilities when planning services for disabled students (PALS).

Levels of Inclusion

The following list comprises the different levels of inclusion for students with special needs. Only the first two qualify as inclusive education:

1. Full inclusion with in-class support - The student is with the regular class all the time, and the in-class support is provided by the regular classroom teacher or teaching assistants, and sometimes by specially trained professionals.

2. Partial inclusion with pull-out programs - The student is usually with the regular class, but they are sometimes taken out of class and given special support, either individually or in small groups

3. Self-contained classrooms comprised of students who all have special needs

4. Special day schools where the entire school is comprised of students with special needs

5. Residential schools where the students' needs are severe enough to require round-the-clock support

6. Hospitals or home care

In the case of the latter two points, inclusive education is not feasible. The debate concerning inclusion pertains to the first four points: should students with special needs be included in regular classrooms or in separate classrooms or schools, and if they are included in regular classrooms, should they be included all the time or just part of the time? (If students are violent, they are not considered to be acceptable candidates for inclusive education) (O'Donnell 132).

Individualized Education Plans

In Canada, whether special needs students are included in regular classrooms or not, all of them are given an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) created uniquely for them. The IEP is determined at the beginning of each school year by a team consisting of the parents, the child's teachers, the school psychologist and a special education consultant. The IEP includes

- measurable goals for the year

- a specific plan for achieving those goals

- the support that the child is supposed to receive

- the degree (if any) of inclusion in the regular classroom

The IEP also states whether the curriculum will be modified for the student. If the student does the same work as the regular students but simply receives extra support in doing it, they will receive a regular high school diploma; if the work is modified, they will receive a different diploma (O'Donnell 132).

Inclusion in Quebec

Inclusive education is tied in with progressive education. Progressive education is used in Quebec's Education Reform, which was created in 1997 and implemented beginning in 2001. Progressive education is an approach to education which focuses on group work, problem solving, hands-on learning, critical thinking and development of social skills. Quebec's Reform did not directly address the issue of special needs students; therefore, in 1999 the Ministry of Education published a plan of action for special education, which focused on the inclusion of special needs students in regular classrooms. In a progressive and inclusive school environment, "everyone is exposed to a 'rich set of activities,' and each student does what he or she can do, or what he or she wishes to do and learns whatever comes from that experience" ("Inclusion").

At the elementary level in Quebec, inclusive education is implemented as much as it is deemed possible. At the secondary level, regular students and most special needs students are streamed into regular and advanced levels in the three core subjects, English, French and math. (For the non-core subjects, there is no streaming.) Shaun was able to go in advanced courses because his disability does not affect his cognitive functioning, and any issues related to social interactions were minor. However, most special needs students in inclusive environments go into the regular stream, because even if they have high cognitive functioning, if they have attention or behavioural problems, those will affect their learning and will already have affected their academic level by the time they get to high school.

At some schools there are one or more other alternatives for special needs students: at the school where I teach there are two special classes for students with behaviour and attention problems who are doing either regular or modified work, depending on the student; two classes of work-oriented students who are doing modified work and have supervised work placements outside the school; and two classes with students who have extensive intellectual challenges. All of these classes have a very small number of students in them.

Advantages of Inclusive Education

Proponents of inclusive education see many benefits to the practice. The first major argument in favour of it is that if special needs students are not included in regular classrooms, that "reduces the disabled students' social importance," because "society accords disabled people less human dignity when they are less visible in general education classrooms" ("Inclusion").

The second major argument in favour of inclusive education is that everyone benefits when special needs students are included in regular classrooms. The disabled students themselves benefit: for example, one study showed that students with intellectual challenges learn more in inclusive classrooms than in segregated classrooms or schools, and their social skills improve as well. Also, schools feel like welcoming places for all students. In addition, proponents of inclusion assert that regular students develop "a heightened sensitivity to the challenges that others face, increased empathy and compassion, and improved leadership skills ("Inclusion").

Disadvantages of Inclusive Education

Critics of inclusive education say that there is a downside to the practice, both for the special needs students and for regular students. Many educators, administrators and parents have reservations about it. Most of the concerns are not with inclusion in principle but in the way it is put into practice.

One issue is that many special needs students need individualized instruction, so often the regular teacher is teaching at the front of the class while the special needs educator is teaching special needs students at the back of the room, and that is not true inclusion, therefore the inclusion has not achieved its objective.

As well, some special needs students require highly controlled environments. Shaun was able to function acceptably in a regular classroom, but students who have attention problems or sensory processing disorders may find a regular classroom too chaotic to function sufficiently well, especially where progressive education methods are used. That can affect the students' academic progress and could also result in behaviour issues which could hinder the regular students as well ("Inclusion").

When implemented properly, inclusion should not cost less than when special needs students have their own classrooms, because the special education professionals are supposed to move into the regular classrooms along with the special needs students, and there are also supposed to be a sufficient number of attendants to assist them ("Inclusion"). However, the reality is that often that is not the case, and special needs students are frequently left in the regular class with no extra support. I have worked at several different schools, and they have all been seriously lacking special education professionals and attendants because there is simply no budget for it.

As a result, it is frequently left to the regular teacher to try to meet the needs of both the special needs students and the rest of the class. Unfortunately, when the teacher is spending time on the special needs students, that time is taken away from the class as a whole, which therefore hinders their learning, and if the teacher does not spend that time with the special needs students, those students will not be making the progress that they could be making and it could also lead to behaviour disruptions which have an impact on the entire class. (Even if an attendant or special education professional is in the classroom, there are still often behaviour issues, particularly since they usually have a number of students to take care of.) There is also a concern that teachers are not adequately trained how to deal with the problems that special needs students sometimes manifest, nor how to adapt their lessons to effectively integrate them. As well, the wide range of abilities in the class means that students on both ends of the scale are sometimes going to be left short: the higher ability students may not be challenged enough, and the work may be too difficult for special needs students ("Pros and Cons").

Advocates for inclusive education acknowledge those points but nevertheless maintain that "even if typical students are harmed academically by the full inclusion of certain special needs students,...[that] is always less important than the social harm caused by making people with disabilities less visible in society" ("Inclusion").

Some people, however, do not agree that special needs students should be exposed to regular students in this way, because not only do some of them fail to make the academic progress that they could be making, they can also be harmed socially and emotionally by the experience. Special needs students are sometimes embarrassed by their limitations and the adaptations that those limitations require. One student that I had would act out and make it seem as though he was just a troublemaker in order to hide the fact that he was behind academically because he had had cancer and did not want anyone to know about it (yet he was kept at grade level, ostensibly to protect his self-esteem). To compound the problem, I was not informed about it until a couple of months into the school year due to a communication error. (Everyone is stretched to the limit in the public school system.). As well, even if regular students are sensitized to special needs students, they could still be made fun of; therefore, some people believe that they should be protected from that in their own classrooms.

Conclusion

Society has come a long way since the days when special needs students were segregated in separate schools or simply fell through the cracks. Julie Hobbs of Education Canada draws a striking contrast between the former way of approaching special needs education and contemporary success stories of the beneficial effects of inclusion when it is done right.

The concerns that people have about inclusion are generally not philosophical but practical: many who are involved with special needs students feel that society is rushing too fast to follow the inclusion trend, because the long-term outcome of these kinds of educational decisions will not be seen clearly for many years.

As well, the decision to implement inclusive education may be based on presumed budgetary savings. "High rates of education are essential for countries to be able to achieve high levels of economic growth" ("Education"); however, when it comes to investing money in it, education is not usually society's primary concern.

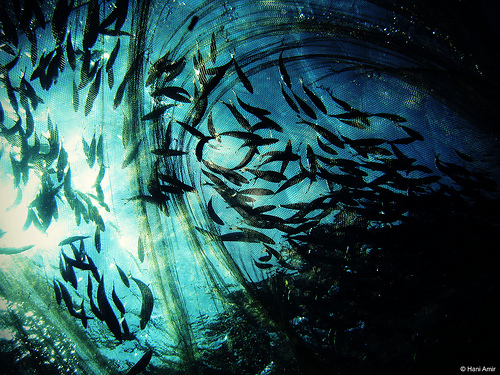

In addition, many feel that not enough consideration is being given to whether inclusion is the best option for each individual student, and not enough effort is being made to ensure that adequate supports are in place to increase the chances of the success of the inclusion. When implemented prudently, inclusive education is probably a great idea for society - but the net should not be spread too wide, and it should be reinforced!

Photo credits: Flickr (students, fish net)

Bibliography

"Adapting Our Schools to the Needs of All Students, Policy on Special Education." Ministère de l'Éducation, 1999. Web.

"Asperger Syndrome Fact Sheet." National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. National Institutes of Health, n.d. Web.

Branswell, Brenda. "Advocacy: 'School can be gruelling for someone like me' Teen Tells Peers." www.aspie-editorial.com. The Montreal Gazette 13 April 2011. Web. 21 Feb. 2012.

"Conditions for Greater Success." Éducation, Loisirs et Sports Québec.Web. 3 March 2012.

Hobbs, Julie. "Inclusive Education: Lessons from Quebec's English Sector." Education Canada 52.1. Web. 21 Feb. 2012.

Houston, Whitney (perf.). "The Greatest Love of All." Whitney Houston. Arista, 14 March 1986. Web. 21 Feb. 2012.

Inclusive Education Canada. Web. 15 Jan. 2012.

"Inclusion: The Pros and Cons." The Southwest Educational Development Laboratory (SEDL) 4.3. Web. 21 Feb. 2012.

Jordan, Anne. Introduction to Inclusive Education. Mississauga, ON: John Wiley & Sons Canada, 2007. Print.

O'Donnell, Angela M., et al. Educational Psychology: Reflection for Action, Canadian Edition. Mississauga, ON: John Wiley & Sons Canada, 2008. Print.

"Participation and Activity Levels Survey (PALS)." Statistics Canada: 3 Dec. 2007. Web. 21 Feb. 2012.

Porter, Gordon L. "Making Canadian Schools Inclusive: A Call to Action." Canadian Education Association: 48.2 (2008): 62-66. Web.

"Teen with Asperger's speaks about stigma, struggle." CTV Montreal: 24 April 2011. Web. 21 Feb. 2012.

Wikipedia contributors. "Education." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 23 Feb. 2012. Web. 23 Feb. 2012.

Wikipedia contributors. "Inclusion (education)." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 1 Feb. 2012. Web. 21 Feb. 2012.

Wikipedia contributors. "Progressive education." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 7 Feb. 2012. Web. 21 Feb. 2012.

Leave a comment