They speak French. Some of them send their children to French schools to preserve their language. They have their own flag, their own culture, and their own history.

They also live in Saskatchewan.

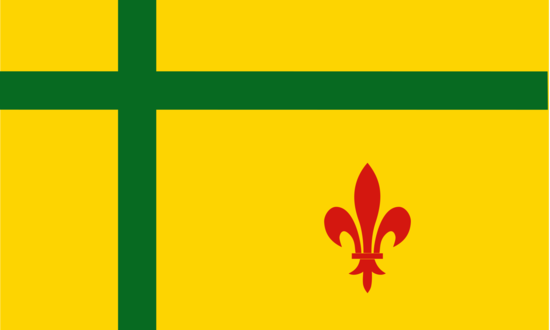

The Fransaskois may not have the numbers that the Quebecois or even the Franco-Manitobans, but they are still an important part of Saskatchewan's history. The province has small settlements and hamlets that are entirely francophone as well as towns and cities that have sizeable, sometimes majority, Fransaskois populations. Everywhere the Fransaskois are, they celebrate their language and unique origins as proudly as any Quebecois.

The French have been moving into the Prairie Provinces for centuries. Like their fellow English Canadians, they came for opportunities, jobs, and new lives in the west. While the first wave of French settlers came primarily for the furs in the area, the next--nearly a century later--moved to the prairies as a part of a push for immigration by the Catholic Church. Most of these people were farmers, and most were dedicated to their language and their religion in equal measures. Their unique prairie life was not assimilated by the largely Protestant English settling around them, and the French population of Saskatchewan in the early 1900s quickly grew to fifty thousand.

These days, the Fransaskois number around eighty-five thousand, with most living in Saskatchewan. Zenon Park is a small bilingual village that once was nearly all French, having been settled by Quebec immigrants coming to work in agriculture and logging. One former resident of the village is Debbie Grassing, who grew up in one of Saskatchewan's French households. At that time, there were only a few families who couldn't speak any French, and though almost everyone was bilingual, she didn't learn English herself until first grade.

"It wasn't that gradual," Debbie says. "We had one hour of French a day, and most of our other classes were all in English." Though she had some bilingual teachers to help them, Debbie says there were no modern-style immersion programs back then. By the time she was in grade two, televisions were more popular, and everyone's English rapidly improved from there. "We didn't know any different," Debbie says; to her and all the other kids of Zenon Park, the whole world must have been learning two languages.

One of the biggest differences between Saskatchewan's French communities and Quebec is the regional language differences. "I think out west here we incorporate more English words into our language as we go along," Debbie says, which is a result of being surrounded by English-speaking people. Most of Zenon Park's resident's parents or grandparents had been from Quebec, and they each brought their own regional French dialect when they came for jobs.

Separated from Quebec, the French language in Saskatchewan grew in its own way, to the point where the Fransaskois accent is unrecognizable to French speakers in Quebec. Once, on a school trip to Quebec, Debbie found that Montrealers knew that she wasn't from there, but they couldn't tell where she was from, either. They had never heard a French accent from Saskatchewan. Interestingly, the French in New Brunswick resembled her own far more than the French in Quebec did.

The Fransaskois population is comparatively small, even in relation to neighbouring Manitoba's French population, and smaller communities become isolated from each other, which can make passing on the Fransaskois culture hard. The school system is helping to keep the language itself alive in Saskatchewan, but French Saskatchewan is about more than just the language.

Though on a smaller scale, French communities in Saskatchewan can relate to Quebec's own struggles to keep the French culture alive. "It's very difficult for students if one of their parents isn't French, because it comes with a certain culture, also, not just the language," says Debbie. She taught her own children a few French words, but they aren't fluent. Just as television taught her generation how to speak English, the internet has taught the young residents of Saskatchewan's French towns, starting at much younger ages. Speaking French at home is rarer now, too, as it's more and more common for Fransaskois to marry an English person.

There is hope, however. The Association Communautaire Fransaskois works to unite Saskatchewan's French population, and there is a regular French paper called L'Eau Vive that circulates around the province. Fransaskois can also tune into Radio-Canada for French programming on radio and television, some of which is even produced in Saskatchewan. French language arts festival and groups for anything from folk arts to fine theatre offer Fransaskois opportunities to express themselves creatively. Saskatchewan's French residents may have to work harder to hold on to their culture, but they aren't giving up.

"Open your eyes," Debbie says to the people who don't know about Saskatchewan's French communities. "Everywhere you go there are different cultures, and there are a lot more French people out west than Quebec people realise."

Leave a comment